The Syrian regime has once again proven to be a force to reckon with in the politics of the Middle-East.

Just as the Russian-led Sochi conference ended in a deal between the host, Iran and Turkey, while the regime was side-lined, it struck back.

It’s not the first time the Assads have managed to bring the country back into the game from a seemingly unattainable position. While it was absent from the negotiation table in south-Russia, and understandably worried because of it, Damascus quickly understood that it could find leverage elsewhere.

The regime has great experiences and successes in turning opposing sides against each other for its own benefit. Syria was heavily invested in the civil war in Lebanon, a country which once formed a part of Syria before the Anglo-French carve-up of the region and whose politics and economy are still intermingled with its bigger neighbour.

* * *

Turning Syria into a regional power

For decades, Syria has been a far greater regional power than its resources, size and population suggest. That wasn’t always the case. In the first years of Hafez al-Assad’s rule, Syria was weakened by the multiple Israeli wars and defeats. Anwar Sadat’s Camp David accord abandoned Syria along with the Palestinian cause. Syria was left alone to deal with the Palestine question and Israel. Surrounding Damascus, both Iraq and Jordan were hostile and Lebanon on the brink of eruption.

Hafez al-Assad (Bashar’s father, dead in 2000) understood that for his regime to survive he needed political legitimacy which he aimed to gain through achieving (or pretending to achieve), the goals of his neo-Baathist party: pan-Arabism and recapturing the Golan from Israel. Lebanon was an obvious choice for Syrian power projection as all the other neighbouring countries were hostile. With its many minorities and common Syrian history, Damascus felt that Lebanon belonged to them. Moreover, Beirut was regarded as a safe haven for Syrian political refugees, investment went both ways and their leaders visited each other, with Syria heavily influencing the composition of the Lebanese government and military.

Three months after Hafez al-Assad’s January visit in 1975, the Lebanese civil war broke out during the spring.

As the country quickly descended into anarchy, the leaders of the various military factions flocked to Damascus for support. Assad was in a perfect position to influence and manipulate the various parties and gain a stronger foothold. The Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) and Sunni leaders faced off against the Christian Maronite and Druze groups (who also fought each other) and various tribal and political armed groups emerged, all seeking a protégé in the Syrian regime.

For Assad, the stability of Lebanon was key for his own regime’s survival, and a battlefield in the confrontation against Israel. Various Israeli military incursions in the sovereign territory of Lebanon has left the components of the fragile society suspicious of each other, with the Maronites blaming Palestinian refugees, and Assad believing that the turmoil was of Israel’s making. He could neither afford a failed neighbour state in a prolonged conflict which would ultimately weaken his own power and give opportunities to his arch-rival.

Assad was in a precarious position in 1976, as the Druze, the Palestinians and the Maronites, (the latter two his supposed allies) emerged as the major armed forces against one another.

Just, six years earlier, Assad entered the Jordanian battlefield during Black September in favour of the PLO, who rose up against the Hashemite Kingdom. However, in Lebanon he had other calculations. The Druze leader, Jumblatt sought to create an Islamist alliance with the PLO against the Maronites, an idea which Assad dreaded for various reasons: if the Palestinians became too powerful, it could spark an Israeli attack and a religious Islamist onslaught on Maronites could bring a foreign intervention. The 1st of June 1976, the Syrian army entered Lebanon to protect the Maronites (from the PLO), with an unwritten allowance from Israel and the US.

The intervention itself, was highly unpopular. The Syrian regime, has based its legitimacy on protecting the Palestinian cause was now at war against them in Lebanon. It was difficult for the public to swallow both at home and abroad. Nevertheless, the Syrian regime was a brutal realist in Lebanon: geopolitical manoeuvrings were more important than ideological alliances with weak partners. The Syrian army started to act as a diffuser in the war: keeping in check the Palestinian and Maronite militias at the same time, while resisting Israeli pressure.

With his intervention, Assad began to set the stage on becoming the main power broker in the Levant and put in motion the Baathist idea of Greater Syria. When the war dwindled down in 1990, the Syrian regime succeeded in bringing much of Lebanon under its orbit.

Damascus kept their army in the country and had the last word in the composition of the government and security apparatus.

Hafez al-Assad was obsessed in making Syria a country reckoned with regionally. Influence in Lebanon was one side of the story, containing Israel was the other.

The reason for Syrian regime’s turn against the PLO was because of the latter’s recklessness in cross border attacks on the Jewish state. Just as today, every skirmish, no matter how small, brought on a much bigger, and in many times unfolded, counter attack. At that time, Syria was in no position to defend itself militarily and every defeat bought on a backlash from the domestic population. Damascus needed to control the insurgency against Israel, not be a victim of it.

During all of his lifetime, containing the Palestinians was a nuisance for Hafez al-Assad. He made sure that the Golan heights became the most militarised zone in Syria, which prevented any cross-border raids. Later, by advancing his grip on Lebanon, the regime solidified its western front and began heavily influencing Shiite groups harassing Israeli forces, until 2006. That year, the Israel-Hezbollah war erupted, just two years after the last Syrian troops left the country.

A change in Bashar’s strategy?

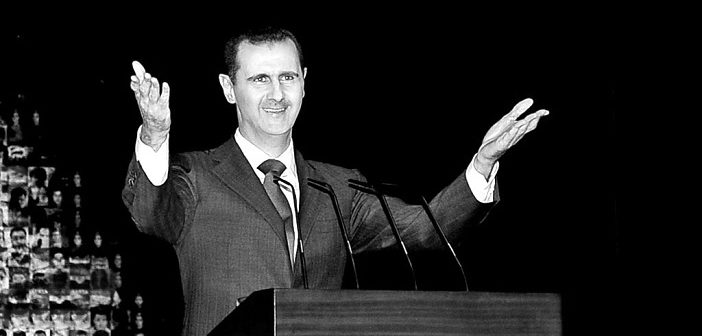

Since his son, Bashar al-Assad inherited power in 2000, the regime continued the same kind of strategy, which has worked so well in the past.

Fierce rhetoric inside Syria went hand-in-hand with a secure border with Israel. Attacks by Israel, such as the bombing of a nuclear facility in Deir ez-Zor in 2007, received no back-lash. The escalation of the current civil war and the rise of the Lebanese Hezbollah and Iran in Syria also brought monthly Israeli airstrikes. There is no question of the illegality of these airstrikes. There has been no declaration of war and no offensives by regime affiliated forces against the Jewish state. While the casualties of the Israeli aerial campaign number in the hundreds, no Israeli civilian has died. Up until now, the Syrian regime has been well aware of the threat posed by Israel and has only tried half-heartedly to defend its installations with aging surface to air missiles provided by Russia.

Up until February of 2018, it seemed that Bashar al-Assad’s regime was determined not to drag Israel into an open conflict. This thesis was challenged with the downing of the Israeli airplane.

Just after 4 in the morning on the 9th of February 2018, an Iranian drone entered Israeli airspace from the Syrian border. An Israeli helicopter intercepted the drone and F16 aircrafts were deployed to neutralize its control centre. The Syrian regime was well-prepared for this event and (rather old) S-200 surface-to-air missiles were awaiting the incoming attack. Several dozen missiles were launched on the target, which eventually brought it down deep inside Israeli territory. While S-200s have been activated in previous Israeli assault, never before in this magnitude or success.

The calculating nature of Bashar al-Assad’s regime has never been put into question. Every major event during the civil war has been thought through in advance. Such was the case starting from the first-time a tank, a jet, or chemical weapons were deployed. The goal is always the same: regime survival and power maintenance.

Timing for each “event” is essential and contingency plans are ready well before. Foreign media has also been activated to create a grey zone.

In the month after the Ghouta chemical attack in 2013 which was blamed on the regime, Bashar gave six interviews only in the following month and an additional four more until the end of the year. That is ten in four months. In the following year he gave three in total and nine for the entirety of 2015.

* * *

Bashar al-Assad, along with the regime’s old- and new-Guard have kept their seats for the past seven years because of their capability to set in motion high-risk and high-reward manoeuvres. Thus far, at every instance they’ve succeeded in solidifying their grip on power. They know that one bad calculus will mean their end. They feel that in a war of this nature, and having so many enemies, they must go all in.

As Bashar al-Assad said in a speech in Damascus Opera House five years ago: “We’re up against a war in the full meaning of the word.”

It’s a zero-sum game.