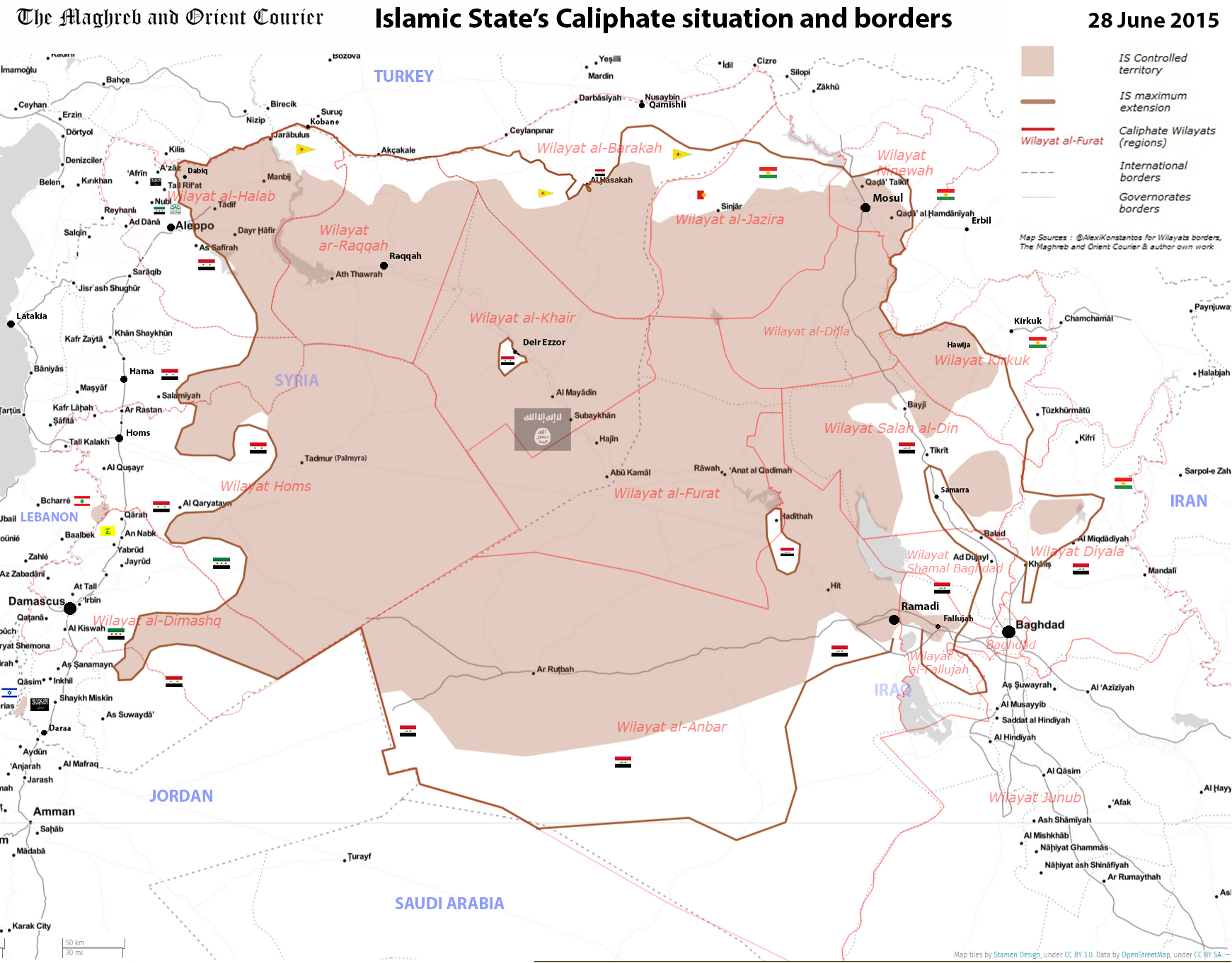

In June 2014, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of the Islamic State (IS), announced the restoration of the caliphate and created a de-facto political entity over the main parts of Iraq and Syria.

This announcement followed the Islamic State’s take-over of Mosul in Northern Iraq, which was the biggest city the group ever controlled. After the rapid development of the IS in Iraq in June 2014 which ended in the capture of huge territories, almost reaching the gates of Baghdad, the Caliphate extended from the Turkish border in the North to the Saudi Arabian border in the south, and from the Syrian desert in the West to the Iraqi Kurdistan outskirts in the East. One year later, despite fighting versus all parties in Syria and Iraq, and the entry of the US-led international coalition in the war, the Islamic State has managed to keep control of an important territory, advancing in some areas while retreating in others.

Click on image to enlarge it

The defeats

Most of the IS setbacks came from Kurdish-inhabited areas, areas defended by Kurdish militias such as YPG (Syria) or Peshmergas (Iraq).

After the almost complete take-over of the Kobane Kurdish enclave, in the North of Syria, in October 2014, the IS had to retreat from the area in the beginning of 2015, challenged by heavily-motivated Kurdish fighters, as well as daily bombing, more and more precise,of the international coalition. In December 2014, a Peshmerga offensive liberated the besieged Yazidis in Mont Sinjar, showing for the first time military operations coordination with YPG and Yazidi militias, as well as Christian Assyrian militias.

The front stabilized for a while in the North-East of Syria (the Jazeera), until the IS managed in February 2015 to advance in some areas in Assyrian-inhabited Khabur valley West of Hasakah, occupying some villages on the South bank of the Khabur river, taking some dozens of civilian hostages. This situation of war in the Khabur region, close to the strategic city of Tal-Tamer, led to the launch of the YPG “Robert Qamislo” offensive, starting on May 6, 2015, with the participation of Christian militias (situated South of Khabur), reaching eventually Tall Abyad in June 2015, and allowing the Kobane and Jazeera (Cizire) YPG troops to joineach others, cutting IS access to the Turkish border East of theEuphrates river, who now only holds the border post of Jarabulus, the only point of contact with Turkey.

In the Eastern front in Iraq, the IS showed strong resistance on the Mosul – Hawija front-line with Iraqi Kurdistan, but lost ground in the Tigris valley where the Iraqi army, helped by Shia militias, managed to take back Tikrit at the end of March 2015. There the IS had not yet settled properly and was hence driven out of the economically important zone of Baiji (petrol refinery), in June 2015.

The gains

The IS rapidly picked up the offensive in Iraq and took the initiative in the Euphrates valley, taking over the provincial capital Ramadi in May 2015, increasing their presence in Fallujah, which the IS already held, not far from Baghdad. The only remaining Iraqi government controlled area is Haditah, to the East of Ramadi, and its strategic dam on the Euphrates.

The IS managed to advance on the Western front of the caliphate in Syria, mostly at the expenses of the Bashar al-Assad Government, which lost huge areas in the Syrian desert following the Palmyra offensive in May 2015, and kept heavy pressure on remaining government-controlled gas fields, air bases and supply roads, East and North of Palmyra. And in Hasakah, a heavy offensive was about to end loyalists presence in the city at the time of writing this article.

The IS also progressed at the expense of Syrian rebels of the Free Syrian Army, but experienced irregular results. In the Aleppo governorate, where the rebellion is dominated by the Islamic Front and Jabhat al-Nusra (Al-Qaeda branch in Syria – of which some parts have joined the IS already in 2013), the IS advanced recently in some villages, closing in on Aleppo, but had to face a strong resistance from embattled rebels defending their main Azaz – Aleppo supply line with Turkey.

In the Syrian Desert, particularly in East-Qalamoun, the IS managed to take over some areas following the Palmyra offensive; and this 25th of June, the IS forces, coming back in Kobane region, have also conquered the mostly part of the city of Hassakah, opening the door of the Jazeera (North-East of Syria).

In some other locations, they were less successful: in Quneitrah, where an IS affiliated group was expelled by Jabhat al-Nusra, and in South Daraa, where Liwa Shuhada al-Yarmuk was suspected to swear allegiance to the Islamic State, and had to retreat from some towns following clashes with Jabhat al-Nusra; in Qalamoun near the Lebanese border, where a joint operation from Hezbollah and the Syrian army led to the IS retreating to the Arsal rocky mountains, and in Damascus itself where several attempts by the IS to activate dormant cells in rebel-controlled areas, or to take over the Yarmouk refugees camps, were all unsuccessful.

The factors explaining the advance of the IS

Regarding the factors of success or failure of the Islamic State in the past year, one has to admit that the presence of non Arab Sunni minorities represent a heavy obstacle for the expansion of the caliphate; as most of the areas inhabited by Alawites, Chiites, Ismaelites, Yazidis, Assyrians, and Kurdsresist the IS advance and are kept out of Islamic State control. Also, the international coalition air strikes were a key factor in helping Kurdish troops and Iraqi troops move quicker through the terrain, to attack IS supply lines and totake back control of several cities. The other resistance factor is probably the Jihadist in-fighting with Jabhat al-Nusra.

On the other hand, several factors explain the successes of the Islamic State. The first is the support given to the IS, if not the massive approval, from several Arab Sunni tribes in Iraq and in Syria, and it has a strong capacity to generate “allegiance” from other rebels groups that respectively fight against the pro-Shia regime in Baghdad and the al-Assad regime in Damascus. The second factor is without doubt the weakness and low morale of the Syrian government army, tirened by four years of war, as well as the struggling Iraqi army, dominated by Shiites, in hostile Sunni territories such as Ramadi.

Finally, the third factor, without doubt essential, is that the Islamic State has set up a decentralized territorial organization, made up of “Wilayats” – semi-autonomous regions, which (importantly) regroup in some cases former parts of Syria and Iraq, thereby annulling the previous borders; this organization of the state in auto-administered provinces allows the populations to organize their economy in an efficient way, and permits the IS to maintain military activity along almost all of the multiple front-lines, on which they are engaged.

En juin 2014, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, le chef de l’État islamique (EI), annonçait la restauration du califat et créait une entité politique de facto, à cheval sur l’Irak et la Syrie.

Cette annonce faisait suite à la prise par l’EI de Mossoul, dans le nord de l’Irak, la plus grande ville contrôlée par les djihadistes. Les vastes territoires conquis en Irak s’ajoutaient à ceux déjà contrôlés en Syrie ; le califat s’étendait alors de la frontière turque, au nord, à la frontière saoudienne, au sud, et du désert syrien, à l’ouest, aux portes du Kurdistan irakien, à l’est. Une année plus tard, malgré l’hostilité de toutes les autres parties armées en Syrie et en Irak et l’entrée en guerre d’une coalition internationale menée par les États-Unis, l’EI a non seulement réussi à garder le contrôle de la plupart des territoires conquis, mais aussi à s’étendre sur de nouvelles régions, se retirant de certaines zones où il était encore mal implanté, mais progressant ailleurs de manière spectaculaire.

Les défaites

La plupart des défaites de l’EI eurent lieu, en effet, dans les territoires voisins des régions habitées par les Kurdes ou défendus par les milices kurdes, telles que le YPG en Syrie ou les Peshmergas du Kurdistan irakien.

Après avoir quasiment conquis l’enclave kurde de Kobane, dans le nord de la Syrie, en octobre 2014, l’EI dut se retirer de la zone au début de l’année 2015, sous les coups combinés d’une armée de combattants kurdes du YPG ultra-motivés et des bombardements quotidiens et de plus en plus précis de la coalition internationale. En décembre 2014, les Yézidis, minorité religieuse non musulmane, assiégés par l’EI dans les monts Sinjar, furent libérés par une offensive des Peshmerga d’Irak, combinée avec une offensive YPG du côté syrien, ainsi qu’avec la participation de milices armées yézidies et chrétiennes assyriennes.

Après une courte stabilisation du front dans le nord-est syrien (la Jazeera), l’EI reprit l’offensive en février 2015, en s’emparant des villages assyriens situés sur la rive sud de la rivière Khabour, et prenant en otage plusieurs dizaines de civils. Cette situation de guerre permanente sur la Khabour, aux portes de la ville stratégique de Tal-Tamer, conduisit le YPG à lancer l’opération « Robert Qamislo » le 6 mai 2015, avec la participation des milices chrétiennes (MFS et Khabour Guards) ainsi que de la tribu arabe al-Sanadid. Cette offensive progressa rapidement jusqu’à repousser les combattants de l’EI dans les monts Abd al-Aziz (situés au sud de la Kahabour) et finit par atteindre Tal-Abyad, permettant ainsi aux armées de Kobane et de la Jazeera (Cizire) de se rejoindre et de constituer un contrôle kurde ininterrompu le long de la frontière turque, de l’Euphrate jusqu’au Kurdistan irakien, l’EI ne contrôlant plus alors que le poste frontière de Jarabulus, à l’ouest de l’Euphrate, son seul point de contact avec la Turquie.

Sur le front de l’est, en Irak, au pied des montagnes du Kurdistan, l’EI a fait preuve d’une capacité importante de résistance le long de l’axe Mossoul – Hawija, mais a perdu du terrain dans la province de Diyala et le long de la vallée du Tigre, où l’armée irakienne, aidée par les puissantes milices chiites, a repris la ville de Tikrit, fin mars 2015, où l’EI s’était encore mal implanté, avant d’expulser aussi l’EI de la zone économiquement importante de Baiji (raffinerie pétrolière), en juin 2015.

Les succès

L’EI a par la suite très vite repris l’offensive en Irak et a repris l’initiative dans la vallée de l’Euphrate, avec la prise de la capitale provinciale Ramadi, en mai 2015, confortant sa position à Falludjah, que l’EI tenait déjà, aux portes de Bagdad. La présence de l’armée régulière irakienne, à l’est de Ramadi, se limite désormais à la région d’Haditah et à son barrage stratégique sur l’Euphrate.

Sur le front ouest, en Syrie, l’EI a globalement progressé, principalement au détriment du gouvernement de Bachar al-Assad, en prenant le contrôle de Palmyre et de la plus grande partie du désert syrien, en mai 2015. En outre, les djihadistes ont exercé une pression quasi ininterrompue sur les derniers champs gaziers et bases militaires détenus par le régime syrien, à l’est et au nord de Palmyre.

Dans le même temps, l’EI a aussi progressé aux dépends des rebelles syriens de l’Armée syrienne libre (ASL), avec des résultats irréguliers. Ainsi, au nord d’Alep, où la rébellion est dominée par une coalition formée de l’ASL et de factions islamistes diverses, d’une part, et, d’autre part, par Jabhat al-Nusra (la branche d’al-Qaeda en Syrie –dont une partie des brigades a rejoint l’EI en 2013 déjà), l’EI a pris le contrôle de plusieurs villages, se rapprochant d’Alep et du fief rebelle d’Azaz, même si sa progression fut enrayée par la résistance farouche des rebelles défendant leur ligne de ravitaillement depuis la Turquie.

De même, dans le désert syrien et dans l’est des monts Qalamoun, l’EI a profité de l’élan de l’offensive de Palmyre pour prendre pied dans les zones rebelles; et, le 25 juin 2015, les troupes de l’EI, de retour dans la région de Kobané, ont par ailleurs fait leur entrée dans la vielle d’Hassakah, porte d’entrée de la Jazeera (nord-est de la Syrie).

Mais, sur d’autres champs de bataille, le résultat fut moins probant : à Quneitrah, où un groupe affilié à l’EI fut expulsé de la zone par Jabhat al-Nusra ; dans le sud de la province de Deraa, où le groupe Liwa Shuhada al-Yarmuk, que l’on suppose avoir prêté allégeance au calife, dut se retirer de certaines positions après des combats avec des factions affiliées à al-Qaeda ; dans les monts Qalamoun, le long de la frontière du Liban, où l’EI est tenu en respect par l’armée libanaise, le Hezbollah et l’armée régulière syrienne ; et à Damas même, où les djihadistes tentèrent sans succès de prendre le contrôle du camp de réfugiés palestinien de Yarmouk et de réveiller plusieurs cellules dormantes.

Les facteurs explicatifs de l’avancée de l’EI

En résumé, à l’analyse des facteurs de succès et d’échec de l’État islamique depuis un an, il faut d’abord constater que les régions où sont présentes des populations non arabes sunnites constituent un barrage important à l’expansion du califat ; la plupart des zones habitées par les Alaouites, Chiites, Ismaélites, Yézidis, Chrétiens assyriens, Druzes ou Kurdes (à l’exception des Turkmènes) résistent fermement à l’EI et demeurent hors de son contrôle. De même, l’intervention de la Coalition internationale a permis à des troupes kurdes et irakiennes, par des frappes aériennes ciblées, de pouvoir avancer plus rapidement sur le terrain en attaquant les lignes de ravitaillement de l’EI. Enfin, la querelle fratricide qui oppose l’État islamique et la branche syrienne d’al-Qaeda, Jabhat al-Nusra, constitue une entrave non négligeable à l’avancée de l’EI.

À l’inverse, plusieurs facteurs expliquent le succès global de l’EI. Le premier facteur est le soutien dont bénéficie l’EI, si ce n’est des foules arabes, du moins d’une partie non négligeable des tribus arabes sunnites en Irak et en Syrie, qui sont en rébellion, respectivement, contre le gouvernement pro-chiite de Bagdad et contre le régime de Bachar al-Assad ; l’EI fait preuve d’une capacité forte de générer des allégeances plus ou moins spontanées d’autres groupes rebelles. Le second facteur est sans nul doute la faiblesse et le moral déclinant d’une armée régulière syrienne épuisée par quatre années de guerre, ainsi que le manque de motivation d’une armée irakienne, dominée par les Chiites, en territoire sunnite hostile, comme par exemple à Ramadi.

Enfin, un troisième facteur, sans doute essentiel, est la capacité qu’a eue l’EI de mettre en place une organisation territoriale décentralisée, constituée de « wilayats », des régions semi-autonomes et –c’est important- qui regroupent dans certains cas des pans de territoires syriens et irakiens (annulant ainsi les anciennes frontières) ; cette organisation de l’État en provinces auto-administrées permettent en effet aux populations d’organiser leur économie de manière efficace et à l’EI de maintenir une activité militaire sur la quasi-totalité des multiples fronts sur lesquels il est engagé.

5 Comments

Pingback: Agathocle de Syracuse | ARAB WORLD MAPS (Islamic State) – The Caliphate keep on growing (En-Fr)

Superbe travail. La carte est hyper détaillée et est à jour. Mais comment faites-vous pour obtenir toutes ces informations ? Comment vérifiez-vous si ces informations sont fiables ? En tous cas, cette nouvelle rubrique apporte un plus indéniable dans la compréhension des événements du Moyen-Orient.

Les informations proviennent la plupart du temps de notre réseau de correspondants dans les différents pays arabes, et d’une connaissance approfondie de la situation du pays concerné par la carte par l’auteur. Nous utilisons aussi parfois des données publiques disponibles, et dans ce cas, indiquons la source. C’est par exemple le cas ce mois-ci des frontières des “Wilayats”, régions administratives du califat de l’EI, dont les contours proviennent du travail d’un historien journaliste, Alexi Konstantos, que nous indiquons dans les sources au niveau de la légende.

En tout cas, merci pour vos encouragements

I think you give IS too much credit. Despite their organisational/operational strengths, I think it is a particularly fortunate configuration of circumstances that have allowed IS to grow in the way it has.

IS is not particularly impressive as a conventional army. They are good however at integrating terrorist/guerilla tactics (assassinations, bombings, suicide attacks) and by utilising Islamic jihadi ideology (married with modern PR techniques and internet promotion), they are provided with inordinate amounts of dedicated cannon-fodder. They are good at identifying soft targets, weak front-lines and the areas with the best risk vs return in loot and/or weapons caches. The history of some of their members in the local intelligence services seems to be key in this skill and network-building ability.

Despite this, a few battalions of regular troops from a professional army would likely beat them very quickly (on the battlefield), but then the real problems would begin, not least if that force was from a non-Muslim nation, as this would be a rallying call to jihadis across the world, provided by the Koran’s unfortunately ‘profligate’ language regarding the legitimacy of fighting non-believers.

The balance of power in Syria has been their principle friend, in that their defeat there would principally benefit Nusra front/IF in Northern Aleppo and the SAA in most areas of central and Eastern Syria, who to varying degrees are openly opposed to liberal human rights ideals or pay lip service to human rights, but are not trusted by Western actors.

The policies of the other actors in the civil war have not been discussed, but they are key to IS’s survival. The SAA has up until recently not focused on IS, as they know that there is no way IS could form an acceptable political alternative. The Kurds are not incentivised to take the initiative against IS in Iraq and have serious bad-blood with the Baghdad administration. Iran’s fondness for brittle ‘hard-men’ autocratic proxies have gone no small way towards alienating and dividing both Iraq and Syria.

The US’s main (inadvertent) contributions to IS seems to be the lack of understanding at the top of key points of culture and history in the region, the belief that they could reshape Iraq as a functioning democracy without UN (multlateral help), under-resourcing the occupation, the indiscriminate sacking of the Baathist security and government apparatus and the imprisonment of major islamists/Baathists together.

The totalitarian ideology and ruthlessness of IS allows them to fight without compunction and to suck areas dry, parasitizing on established social and economic networks, long after the local population would have called for their removal.

They are an incredibly dedicated criminal organisation, which is good at integrating into the fabric of Sunni tribal social life, by way of financial patronage, marriage and threat and has allowed to expand their reach due to unreliable local allies, the configuration of the power-balance and the goodwill afforded to them by their claims of religious legitimacy, fight against perceived oppressive regimes and by basing their actions and narrative on precedents set by Mohammed and the salaf.

In short, if there was a clear political path in Syria, led by actors with credible human-rights credentials, the ability to project their power over the Syrian territory, and some sort of programme for reconciliation for the aggrieved groups, then IS would be relegated back to the marginal conservative social backlash movement they originated as. But alas.

Pingback: Massenbach-Letter: NEWS 10/070/15 | Massenbach-Letter