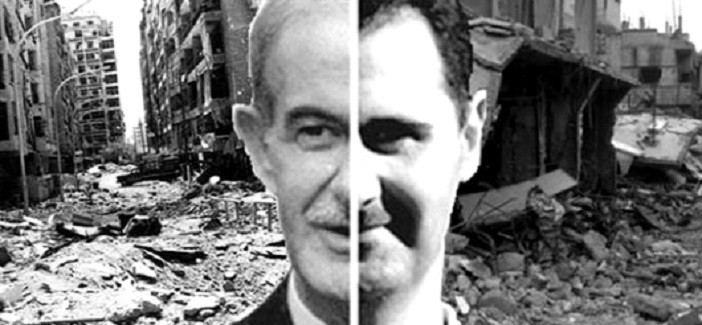

During the Assad family dynasty, the current civil war isn’t the only one that threatened the Alawi power.

The Muslim Brotherhood has been a legitimate political actor in Syria even before the French mandate ended in 1945. The Brethren, or it’s other name, the Syrian Ikhwan have been competing with the Bath party, and its ideology since the 1920s. Firstly by their respective youths clashing on the streets of Lattakia and Damascus, later in quasi-democratic elections, and finally with arms.

What is now being called by the majority of analysts a sectarian civil war, has been ongoing for almost a century with periods of crisis and calm between the two sides. There are two events, which stand out during the long time rivalry between political Islam represented by the Muslim Brotherhood and the Pan-Arab nationalism of the Syrian Baath party.

The first one is the Ikhwan insurgency starting in 1970’s, which ended with the Hama massacre in 1982, and the second is the current civil war.

The Alawites in Syria have had a long-standing relationship and times of confrontation with Sunni leaders in Syria ever since Ibn Taymiyya’s fatwa against them in the XIIIth century. It is because of the Sunni persecution of Alawites that the latter were obliged to flee to the remote mountains of western Syria in the Lattakia governorate. There they settled and formed many small villages, they fought against the Ottoman rulers, and the French colonizers. One of those who fought against the imperialists was Bashar al-Assad’s grandfather, who was the leader of one of the Alawite tribes.

In the 1930s the minority, and historically poor Alawites, took advantage of the French divide and rule policy, and flocked to the army, into the so called Troupes-Speciales. That proved to be a gateway down from the mountains, back to mainland Syria and eventually to political power. The leading Sunni families had the financial means to bribe themselves away from conscription. While this was a convenient choice for wealthier Sunni tribes, it was through the army that Hafez al-Assad managed to gain power in Syria and became the first Alawite ruler in the country. Ever since the assumption of power, the Assad family had to deal with a part of the Sunni majority that did not want to accept living under Alawite rule, calling them heretics,and referring to the famous fatwa by Ibn Taymiyya, who said that they “are greater disbelievers than the Jews and Christians”.

Hafez al-Assad realizing the threat posed to his regime had to implement a strategy to counter the dissatisfaction of his rule by conservative Sunnis in the Levant, which were becoming organized by the Syrian wing of the Muslim Brotherhood.

Hafez al-Assad’s first test came about when he tried to change the Syrian constitution exempting the fact that the head of state had to be a Muslim. As the Baath party’s is radically secular, exempting religion from the constitution was in line with their ideology. However, it was not well received by the conservative Sunni majority in Syria. A series of strikes by the souks in Damascus, Aleppo and Hama followed, and Hafez al-Assad took the middle road by seeking a fatwa from a prominent Lebanese Shi’ite cleric which stated that the Alawite religion is a Shi’ite offshoot, thus the Alawites were Muslims. Thereby there was no need for a constitutional change.

Dissent by a significant part of the Sunnis in Syria continued even after the ruling from the Shi’ite cleric. Protests sprung up, and were led by the Muslim Brotherhood. The Syrian Ikhwan in the early 1970s were organized in three factions, the Aleppo clan, the Damascus clan and the Hama clan, which was the most hard-line one. The Muslim Brotherhood sensing a weakness of the government organized the strikes to become longer, demonstrations more frequent, and preaching in mosques, especially in Hama and Aleppo more and more anti-Baath.

With the relationship between the regime and the Ikhwan becoming increasingly aggressive, and arrests accompanied with torture more wide spread, the Brethren became internally divided. The more moderate Damascus and Aleppo clan wanted their followers to remain peaceful, while the Hama clan looked more and more towards a military approach.

At the same time in the late 1970s a new organisation sprung up next to the Brethren, the Fighting Vanguard, which was, asits name suggests, a military unit. The Muslim Brotherhood leaders thus became fragmented: some of the members took a distance from this new organization, urging peaceful demonstrations, while others joined and approved of the change of tactic.With the violence increasing, the government started to name the Syrian Ikhwan “terrorist and extremist” and agents of Iraq. Officially the Muslim Brotherhood and the Fighting Vanguard were separate organisations, but the regime, and its media didn’t take that into account. They wanted to destroy the Sunni opposition weather peaceful, or armed.

The sectarian nature of attacks by the Vanguards, and most notably that in a military base in Aleppo 1979 changed the nature of the uprising. Captain Ibrahim Yusuf a member of the Vanguard assembled some cadets in a room in the base, and ordered the Sunnis to leave, so that only Alawites would remain. He then opened fire and murdered between 40-82 Alawi soldiers. This action was without the prior knowledge and consent of the Muslim Brotherhood and proved to be the beginning of the end of the Pan-Islamic organisation in Syria. The regime branded this as an attack by the Brethren, and as in the past didn’t make difference between the movements. The government then passed a decree stating that all Muslim Brotherhood members could be sentenced to death. This further divided the Ikhwan, and many gave up their membership, or fled to Iraq and Jordan leaving only the hard core Hama clan now mixed with the Fighting Vanguard as the leader of the organization, standing against the Alawi regime.

From the Aleppo massacre in 1979 and onward, the Fighting Vanguard scaled up their violent attacks against prominent regime officials. Some of the victims include the Aleppo mosque preacher, Hafez al-Assad’s personal doctor, and regime officials in a wide arrange of Syrian towns, in Hama, Jisr al-Shugur, Deir ez-Zoor and Aleppo. With the increasing violence, Syria was on the brink of a civil war. The sectarian nature of the insurgency couldn’t be denied as the overwhelming majority of the victims were Alawites.

To quell the violence, and further divide and isolate the opposition Hafez al-Assad made a couple of well-orchestrated counter measures. By using the wide nepotism of the state, he forged alliances with prominent Sunni businessmen in Damascus. By returning the favour the souks stayed open, and its leaders distanced themselves from the uprising. Hafez al-Assad also implemented more and more Koranic verses in his speeches, trying to portray himself as a devout Muslim. These actions, including the violent clamp down on dissent cornered and isolated the Fighting Vanguard to the central city of Hama.

Several bloody clamp downs by the regime had happened before the Hama massacre of 1982 by the Syrian Arab Army’s elite unit headed by the brother of the president, Rifaat al-Assad. Noteworthy are the Defense Company’s attack on the small city of Jisr al-Shugur in 1980 and the Palmyra prison massacre after a failed assassination attempt on the President in 1981. But the Hama massacre of 1982 stands out on this list as nothing previous can compare to it, neither in numbers nor in level of brutality.

The remaining Brethren having been cornered and isolated by the regime made a last ditch effort to salvage their revolution. Their hope was to spark an uprising in the conservative city of Hama, which would then spread to other cities in Syria, and across the country.

The uprising started with call for preaching in the mosques followed by the handing out of light weapons to the citizens. Ironically the weapons were provided from another, competing Baathist country, Iraq. Soon the rebels attacked party headquarters, executed people allied to the regime, and took over the city. Unfortunately for the Fighting Vanguard their plan proved to be too naive, as the leading Sunni bourgeoisie in the big cities had no interest in joining a full scale armed uprising against the Baathist rulers, thus the rebellion didn’t spread. The complete lock down of Hama made information hard to spread, and the city became completely isolated.

Just like the siege of the southern Syrian city of Daraa in 2011, the army sent soldiers from far away cities to Hama, so that they wouldn’t feel a sense of attachment for the rebel cause. The front line of the assault in 1982 was let by Rifaat al-Assad and his notorious, largely Alawite Defense Companies. The assault started with tank and artillery shelling of entire neighbourhoods. Houses were demolished, often with people inside. The Fighting Vanguard with light machine weapons proved to be no match to the vast Baathist superiority. The infantry moved in and arrested thousands of people, sometimes on ad-hoc charges. In total the death toll ranges anywhere from 10.000 to 40.000 people who were killed in just 27 days. The remaining leaders of the Muslim Brethren and the Fighting Vanguard fled to safe havens in Jordan and Iraq, where the respective regimes provided political cover for them. By the end of 1982 the Muslim Brotherhood in Syria was finished, and attempts to revive the Sunni insurgency from abroad proved to be fruitless.

Although the decade-old insurgency came to a halt in 1982 and didn’t revive until 2011, the memory of the events of Hama still plays a role in the current uprising. It is not only the dead and the martyrs whose memorylooms over the head of the Jihadists today, but the memory of survivors as well. Omar was only 13 years old and a resident of Aleppo in 1980 when he was arrested. He comes from a conservative family but with no political ties. His sheikh in his mosque got arrested a week before him, so a Syrian intelligence agency came looking for young Omar as well who attended sermons. He was held in Aleppo, then transferred to Damascus before being sent to the notorious Palmyra prison. There some prisoners didn’t even survive the journey from the bus to the prison itself as they were kicked and beaten with sticks on the way in. If they fell to the ground, they were as good as dead. Inside the prison every single day would start with beating, humiliation, and torture, which lasted throughout the day, even when someone just wanted to go to the toilet. At the height of the Muslim Brotherhood uprising 60-80 people were executed daily. The prisoners either accused of being Muslim Brotherhood members or Iraqi spies would pray for their death, rather than for their lives.

The ghost of Hama and the prisons of Syria fuelled the current crisis, and the revenge-lust of the Sunni majority. Unlike his father Bashar al-Assad wasn’t able to contain the crisis to only one city, and certainly hasn’t made prison-life humane.

Even if this war will end with a full scale government victory, people just like Omar will survive and tell their story, thus another conflict is all too likely.