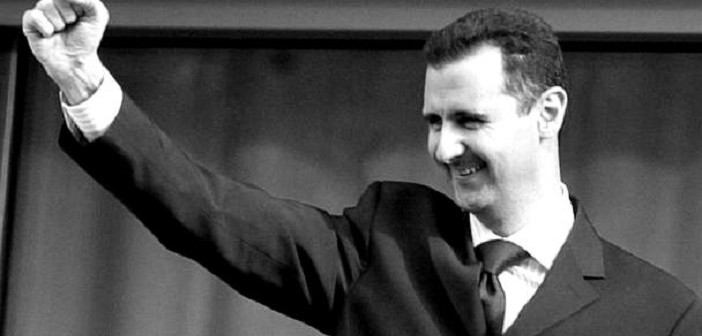

![Syria's Alawites [19116]](http://lecourrierdumaghrebetdelorient.info/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Syrias-Alawites-19116.jpg) As much of the world focused on the salvation of Palmyra’s treasures from the depredations of the Islamic State, much more crucial machinations have been taking place under the surface of the Syrian political landscape. One major development has gone largely unnoticed in Western media but could have critical implications for the fate of Bashar al-Assad and his regime.

As much of the world focused on the salvation of Palmyra’s treasures from the depredations of the Islamic State, much more crucial machinations have been taking place under the surface of the Syrian political landscape. One major development has gone largely unnoticed in Western media but could have critical implications for the fate of Bashar al-Assad and his regime.

In early April 2016 several major European news agencies were approached by a small group of Syrians claiming to represent the interests of approximately 40% of the Alawite sect -the co-sectarians of Bashar al-Assad who make up 10-15% of Syria but are overrepresented within the regime’smilitary-security apparatus. They presented a document, attributed to influential tribal and religious Alawite sheikhs inside Syria, called “Declaration of an Identity Reform”.

Politically this document is vague but fascinatinglyappears to distance the Alawite sect from the regime, without necessarily indicating any substantive move towards the opposition, which it nonetheless describes as “an initiative of noble anger”. Without naming the regime directly, the declaration implicitly proposes a political transition away from “totalitarian rule” to a new era of “democratic… national integration”. The declaration does not explicitly endorse a political or military reorientation but rather seems to be an aspirational statement that the Alawites, as a separate branch of Islam, require a kind of ‘mental revolution’ in order to transcend their ‘persecuted-minority’ mentality if they are to achieve any future security in Syrian lands.

Most astonishingly, the declaration tries to separate Alawism from orthodox Twelver Shiism, saying that “we hereby decline any fatwa that seeks to appropriate the Alawites and considers Alawism an integral part of Shiism…”

This marks a dramatic turnaround from Alawite, Syrian-regime and Iranian efforts to cultivate such anassociation sincethe 1970s. Hence, many Syrians and Syria observers are skeptical about the validity of the declaration, sensing regime subterfuge or opposition misinformation. Indeed, it seems incredible that these Alawite sheikhs could have managed to circulate this document among influential Alawites inside the regime stronghold of North-West Syria, exit the country in order to present it to an international audience, and then slip safely back into Syria. The deep penetration of the security apparatus into all parts of the Alawite community renders it highly unlikely that a wide-based and independent Alawite movement could coalesce without drawing the attention of the ubiquitous mukhabarat. However, after closer examination the timing and context within which it has surfaced raises the possibility that it is genuine and also highly significant.

In recent months Bashar al-Assad has been seeking to leverage off his stronger positionsince the Russian intervention in September 2015. Russian competition with Iran over long term influence in Syria and the region may have played a part in Russian calculations to steal the initiative by intervening directly in Syria. In addition many Syrian military officers and members of the regime’s inner core have increasingly been feeling disrespected and marginalized by Iranian Al Quds and Lebanese Hizballah officers’ sense of superiority vis-à-vis –mostly Alawite– Syrian officers.

In this context the Russian intervention came as a relief to many Alawites, who felt increasingly jammed between a regime prepared to use them as cannon fodder to the end, and an Iranian regime who did not respect their particular form of Islam and who wanted to impose their geopolitical priorities through annexation and subjugation of Syrian independence.

Despite his clear reliance on external support for his survival, Assad still claims to possessbroad legitimacy across the country and insisted on going ahead with scheduled parliamentary elections in regime-held parts of Syria in early April. Assad even made noises about bringing forward presidential elections, not scheduled to be held until 2021 as a way to show that he still enjoys popular support. Russia on the other hand, has priorities of consolidating its hold as the dominant actor in the Syrian arena through alternating brutal force against opposition forces with feints at diplomatic dexterity. Assad’s insistence on holding elections goes against Moscow’s adviceand stands in contradiction of the Geneva process, in which Russia is trying to play the role of chief orchestrator. This has annoyed Russian powerbrokers who are becoming frustrated with Assad’s inflexibility. Russia’s partial withdrawal could therefore be partly understood within this context as a message to Assad that their support to him should not abused and is not a forgone conclusion. There are other reasons for Russian partial withdrawal, including the costs of large-scale deployment on a strained Russian economy, the fact that the mission of shoring up the tenuous position of the Syrian regime ahead of negotiations was largely achieved (ISIS was never the primary target), and the Russian strategy to look like a credible partner to any conflict settlement process.

Within this context the Alawite declaration of identity reform could signal a shifting away from an overdependence on Iran but also the Alawites’ forty-six-year conflation with the Assad family dynasty. Since 1970 the traditional Alawite leadership has become deeply coopted and suppressed by the Assad-Ba’athist regime. However, similarly to the confidence that the French presence gave Alawites to overcome their defensive ‘minority mentality’ vis-à-vis Syria’s Sunni majority in the 1920s-30s, the stronger Russian presence in North-West Syria may have emboldened some of the sect’s current leadership to seek an escape from their inexorable “death-embrace” with the Assad regime.

For Russia, there could also be greater long term strategic and political advantages in forging close ties with the Alawite sect than persevering with upholding Bashar al-Assad, who remains the major sticking point for any new political configuration in Syria. As the most recent attempts at negotiations at Geneva III once again stalled over the question of Bashar al-Assad’srole on April 18-19, both Putin and influential Alawites may have begun contemplating sacrificing Assad in order to unlock the impasse. By inviting the Russian intervention into Syria, Assad may have in fact signed his own death warrant.

Whether the Alawite Declaration of an Identity Reform really represents a groundswell of support for a new direction among Syrian Alawites is still debatable. No significant movement on the ground among Alawites has become visible, although angry Alawite crowds have occasionally protested in Homs and Latakia in recent times, against regime inability to protect them and also against the corrupt excesses of regime elites like Suleiman al-Assad. But does this mean that the document is a fake or perhaps the product of a minority of liberal Alawite oppositionists outside the country? When asked whether he knew about the document, prominent Alawite opposition activist Issa Ibrahim –grandson of the famous Syrian nationalist icon, Sheikh Saleh al-Ali-, stated that he had not heard anything about such a document. This is not necessarily surprising due to the fact that the circulation of the declaration in the Alawite territories would have had to be done in extreme secrecy – a task that may have been made easier by Russian assistance, if that theory is indeed correct.

Other indicators of the validity of the declaration include the nature of the text itself. Alawite religious texts are by definition esoteric and require some degree of interpretation. Thus the oddly old fashioned style and wording of the Arabic original supports the possibility that it is written by the sect’s religious scholars. There is also a historical precedent for these types of statements by Alawite religious scholars when the security of the sect is under threat. For example, the 1936 declaration that defined Alawite identity as Muslim and pushed the sect to accept the unity option of joining with the Sunni dominated Syrian interior instead of separation under French protection.

In the current crisis the question is why did the sect’s leaders wait so long to move, given the perilous position the group now finds itself in? In the case of the 1936 decision there was tremendous debate and division within the Alawite community, it required a major event to shift the calculus; in that case the change came in the form of an unprecedented fatwa from the Sunni Mufti of Jerusalem that effectively welcomed Alawites into the Muslim fold. In the current scenario, not only was the community divided in 2011 –most Alawite opposition activists were quickly isolated– but the regime itself acted strongly to repress any alternative Alawite voices while looking to instil terror into the Alawite sect, and other minorities, of a vengeful Sunni Arab tidal wave.

A major event was required in order to shift Alawite calculations; regime reversals in mid-2012 brought some Alawite misgivings. But the Russian entrance into North West Syria in 2015 was perhaps the major factor that persuaded Alawites that a shift was possible.

On 27 February 2016 a ceasefire began, negotiated mainly through Russian agency and US and UN desperation for any breakthrough. The ceasefire was designed to show Syrian-regime and Russian strength and capacity for influencing events on the ground. However, the momentary lull in the four-year heavy bombing of opposition strongholds instead led to amazing scenes withthe original protest movement emerging in large numbers from bombed out cities and resuming protests in exactly the same fashion as 2011 – perhaps 100 plus separate protests took place in the first days of the ceasefire and continued for the following several weeks.

This showed clearly that the pluralist aspirations of Syrian revolutionaries persisted and not all the opposition had been radicalized. This fact was witnessed with dismay by groups like Jabhat al-Nusra, who had been applying a pragmatic, gradual grass roots approach to instilling their extreme ideology in the opposition areas.

But for Alawites it signalled that potential Sunni Arab partners in a new Syrian compromise still existed. Alawites are not necessarily seeking to become beholden to a new Russian power, similar to how they refused to be entirely subjugated to French authority in the mandate years.

However, there is a real possibility that Alawite leaders are looking to exploit the presence of alternative Russian power to prise themselves free of the Assad stranglehold.